Longer, faster, stronger and HIGHER. A lot of us seek new and exciting adventures. To tick the bucket list, some of us head to the hills for skiing and snowboarding, hike new heights to Everest base camp, or look to summit Mt Kilimanjaro or Mt Fuji. But before any such adventure, it’s important to educate ourselves in the effects of altitude on the human body.

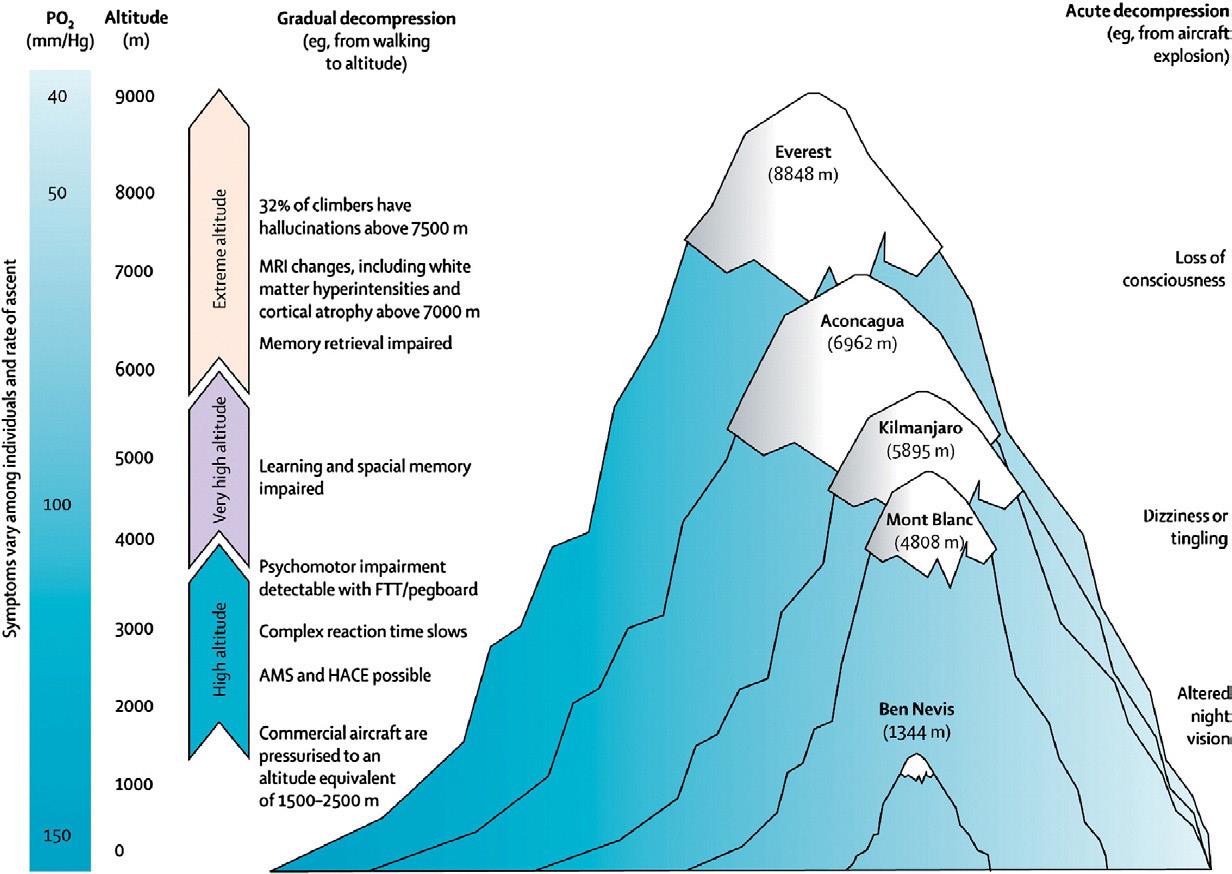

- High Altitude: 1500m – 3500m

- Very High Altitude: 3500 – 5500m

- Extreme Altitude: > 5500m

Acute mountain sickness (AMS) is one thing you definitely need to know about, as it is preventable with the right pre-adventure program, and increasing your knowledge can help in reducing its impact.

Epidemiology and risk factors associated with AMS:

One of the most important determinants of AMS in individuals is their rate of ascent. This is when your ascent is faster than your ability to acclimatise to the conditions. The incidence and severity will depend on this rate of ascent, the altitude attained, duration at that altitude, level of physical exertion, and the individual’s own physiological susceptibility.

Symptoms and signs of AMS include:

- High altitude headache (most common) that worsens at night and with exertion

- Insomnia

- Fatigue

- Dizziness

- Nausea

- Anorexia (loss of appetite)

If not addressed early enough, AMS can progress to high-altitude cerebral oedema displayed by impaired mental capacity, drowsiness, stupor, and ataxia. Individuals can slip into a coma as soon as 24hrs following the onset of ataxia or altered mental status.

I have witnessed all of these on past treks to Everest Base Camp. We stayed overnight at Gorokshep (5140m), and then one person that was sitting by the fireplace to keep warm became unresponsive and slipped into a coma. The Sherpas made the quick decision to carry this individual down to a lower altitude as soon as possible (at the time no helicopters could fly due to poor weather conditions). As the individual progressed down in altitude they began to re-awaken and return to normal function. However, some people haven’t been as fortunate, so it is imperative to work on preparing your body for the situation, in order to prevent AMS from occurring.

Preventative measures include:

- Ascending slowly and allowing for a gradual period of acclimatisation

- Daytime hikes to higher altitudes for individuals not experiencing signs or symptoms of AMS.

- ‘Climb high, sleep low’ has been used to accelerate acclimatisation by intermittently exposing the individual to a higher dose of hypoxia

- Getting some prior altitude exposure. Schneider et al reported that the incidence of AMS fell from 58% to 29% when there was an altitude exposure above 3000m during the previous 8 weeks

- Knowledge of the signs and symptoms of AMS

Happy ascending.

Neurological consequences of increasing altitude

Sources

Brukner & Khan, Clinical Sports Medicine 3E Rev (2009), McGraw-Hill Professional

Imray, C., Wright, A., Subudhi, A., Roach, R. (2010). Acute mountain Sickness: Pathohysiology, prevention, and treatment. Progress I Cardiovascular Diseases, 52, 467-484.